This Peruvian retablo artist has found a way to ensure that the traditional craft he loves so much continues to inspire the world, and he’s bending gender norms to do it.

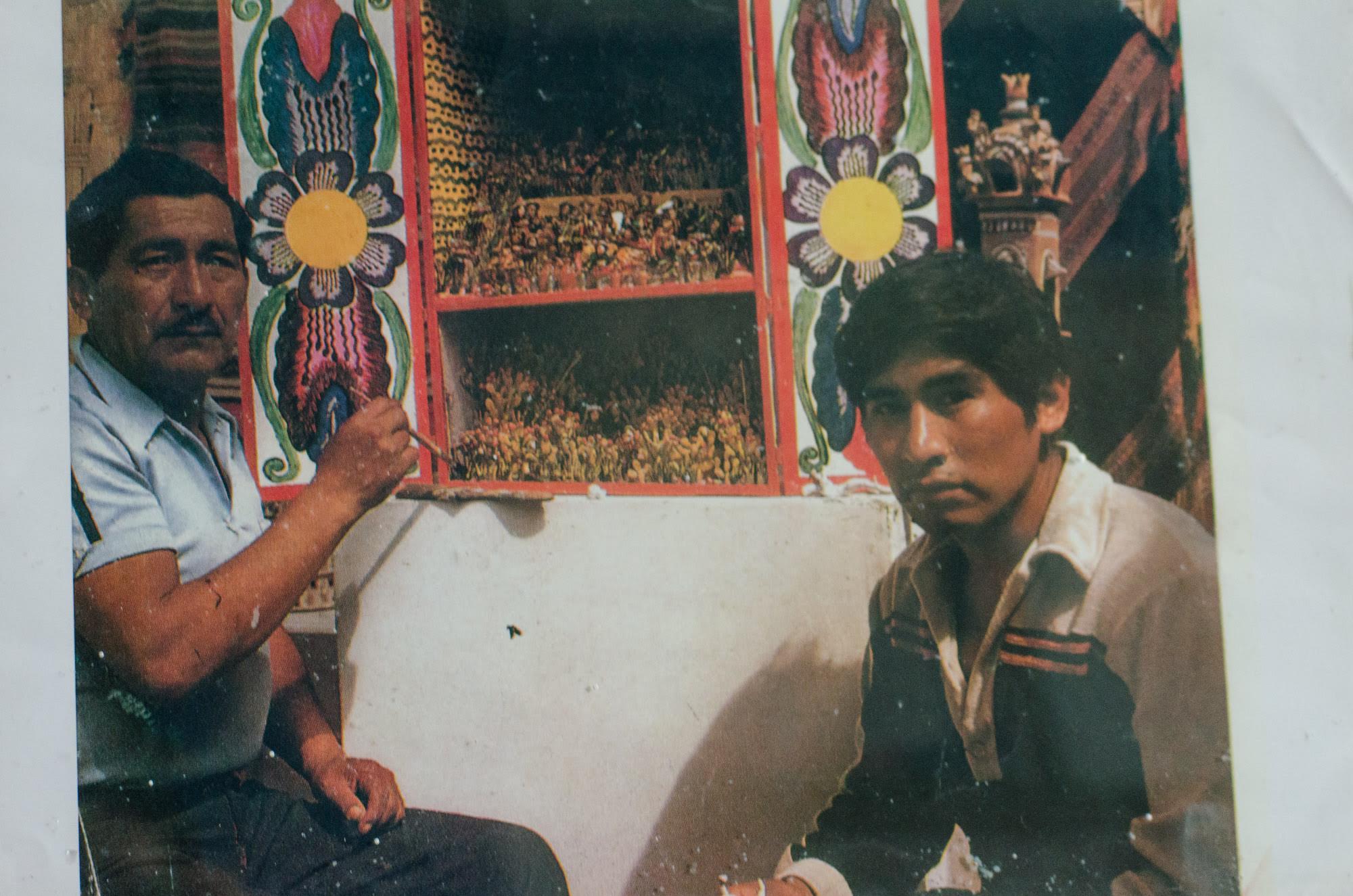

When Jesus Urbano was born, a great master of the Ayacuchan retablo took hold of his hands and uttered a blessing over them. The words seemed to have worked their magic, passing along the gift of the retablo to the young boy.

Jesus, whose father was also a legendary retablo artist, has found a way of life in this beautiful art. He has carried on the work of his father for more than 50 years. Jesus says he’s not afraid to die because he has found a successor — his daughter, who will inherit his workshop when he leaves this world.

Jesus Urbano Cardenas crafts Ayacuchan retablos in his humble home-workshop in the suburbs of Callao. It is a privilege seeing Jesus at work, creating his masterpieces for those who love Peruvian handicrafts, especially folk art aficionados.

He recognizes the great responsibility he carries and must never let go of — that of sharing his last name with a teacher of master artisans, his father, Jesus Urbano Rojas, a retablo artisan renowned in Latin America. The elder artisan passed away in 2014 at the age of 85.

“From the time I first opened my eyes, I was in the workshop. I began this work as play and my father was my only teacher. Thanks to him, I learned all the techniques of this art. Even so, everything I’ve achieved so far will never equal his level. He set the bar really high, but the idea is to continue,” Jesus says as we talk in his home-workshop near Peru’s Jorge Chavez International Airport. There, amid wood boxes stacked atop one another, the retablos begin to take on shape and color.

Son of a legendary retablo craftsman

To say that Jesus was surrounded by popular art is no exaggeration. In Ayacucho, he grew up playing with boiled potatoes, plaster, and small wooden boxes without knowing that ten years later, these would be his principal materials to create Ayacuchan retablos. Although he didn’t yet realize it, the art of the Urbano family flowed in his veins.

“I inherited my passion for this art from my father. In the Sierra, the grandparents have the custom of teaching their grandchildren to carry on our traditions. That’s why, for me, it was easy to adapt to this beautiful art form. Thanks to my father, I learned to depict our customs and stories of the countryside in a didactic manner,” the 53-year-old artisan explains.

Creating a retablo was an exhausting but gratifying job. There were times when the young Jesus Urbano Cardenas took up to six months to complete just one. After finishing it, he’d go to the markets to sell it and received money enough for an entire month. Those were wonderful years when the artisans of Ayacucho could live on what they earned from their art alone. Then the exportation boom began.

“At first, shoppers required quality. A foreigner would pay as much as 500 dollars for a well-crafted retablo. But when Ayacucho’s handicrafts began being exported, everything changed. Art began to lose quality and value. Every month, exporters ordered thousands of retablos and Christmas tree ornaments that we, the artisans, couldn’t make in their time frame. A lot of inexperienced people began crafting retablos using molds for the figurines. This diminished their quality,” Jesus says sadly as he recalls one of the sadder episodes in Ayacucho’s popular art. He makes it clear that his creations are crafted completely by hand.

For this artisan, the retablo is much more than an Andean handicraft – it’s a way of life. This is why he takes such care with each delicate piece and color combination. Even so, his success isn’t due to preserving the family tradition. Innovation is his key to success and, for Jesus, this is the most important moment to perpetuate his father’s legacy.

From altars to retablos

“I like to innovate; I learned this from my father. He was a disciple of the great Joaquin Lopez Antay, the father of the Ayacuchan retablo. My father told me that this master artisan was the first to break the cultural molds of Peru. Lopez Antay was able to convert the traditional religious altars known as ‘boxes of Saint Mark’ into the new Ayacuchan retablos we know today. Can you imagine having a mentor like that? At first, Lopez Antay didn’t want to teach my father but my dad convinced him. In this way, he discovered the world of retablos. But my father took the art a step farther,” Jesus says with pride.

The artistic revolution begun by Lopez Antay hasn’t stopped. The movement was continued by new generations during the 1960s and the art reached the hands of the Urbano family, which disgusted the intellectuals of the time. It is said that the elder Jesus Urbano came to annoy the writer Jose Maria Arguedas with his audacity in differently interpreting Lopez Antay’s traditional retablos.

“I was still a child at the time. I remember that writer Jose Maria Arguedas was upset about what happened with my father and accused him of selling out to commercialism. Arguedas said, ‘All you can do is sell.’ He was angry because my father used bright colors to paint the animals instead of the classic black and white. This made my father sad. But I encouraged him to continue with his artistic vision, telling him, ‘Don’t be silly. Of all the prizes your work has one, Arguedas’ criticism is the best recognition you’ll receive in your life. This will become history.’ And so it was.”

As the years went by, the new retablos became more popular than the traditional boxes of Saint Mark. During that decade, Ayacucho became one of the most visited regions of Peru. Tourists came from every corner of the world.

“In Ayacucho, we had everything. The economy was great and there was no need to move to Lima. I never liked the big city. I’ve always hated the traffic and uproar. I might never have left my homeland if the terrorists hadn’t begun to steal ad kill. But this forced me to leave Ayacucho.”

Jesus Urbano was a young man, only 39 years old. In 1984, Sendero Luminoso or the “Shining Path” had declared war on Peru. It was a time of horror — there were car bombs that destroyed the eardrums and Christmases without electric lights. People died or disappeared every day. It took a lot of faith to see a future in handicrafts, but Jesus didn’t give up. A year after settling in Lima, he began to recover all he had lost in Ayacucho. He also learned to cross the busy streets and lost his fear of the buses.

“Lima wasn’t like Ayacucho. In the country, you can walk freely. In Lima, you had to be very careful with the cars. I quickly got used to it. After a few months, I began to make a name for myself. By the end of the year, I was recognized in the craft fairs. I was invited to participate in art competitions and won them all,” Jesus recalls.

Retablo art will never die out

Today Jesus, the ‘Gentleman of the Retablo,’ lives far from the violence of terrorism. He continues creating and, above all, remembering so he can create the scenes and images for hs retablos. Sometimes he forgets he has a visitor as he concentrates all his attention on his work. He observes his work table as though he were a forensic inspector about to examine a body. Later on, he observes the retablo from all sides. From the look in his eyes, you can see the excitement of feeling like an Apu, an Inca god of the mountains, that looks down on his creations from above.

“We’re like photographers. We see the traditional celebrations and we recreate the humorous images in a retablo. I’ve depicted the Scissors Dance, nativity scenes and shops selling devil masks,” he says, as he explains how artisans immortalize the customs of the Andes.

The years have gone by. Jesus thought he’d arrived at the end of his career. But then he crossed paths with Novica and he could at last do what he’d always wanted — carry on the retablo tradition and spread it throughout the world.

“I find satisfaction in travel and meeting lots of people. When I visit a craft show or exhibition, I don’t go to win, but to share the customs of my homeland. They used to say that master artisans didn’t want to teach. That everything was a secret. But this changed with my father. I enjoy teaching. People are astonished when I tell them that the retablo figurines are made of potatoes,” Jesus confides.

Just as don Jesus learned from his father, his daughter is continuing her family legacy. Katherine Urbano is the only master retablo artisan of her generation. She’s not yet 30 but she has already mastered the family techniques.

“She reminds me of myself,” says Jesus. “That’s what handicrafts are about – to replicate them in future generations so they don’t disappear. As long as there’s passion, the retablo will never die.”